home

needs

local resources

comfort

safety & health

contact

reports

Heat transfer

- Open Fire: Characteristics Of Heat Transfer To A Pan

- Radiation from the Fuelbed

- Radiation from the Flames

- Emission of the soot particles

- Emissivity of the gases

- The total emissivity of the flames

- Convective Heat Transfer to the Pan

- Flow field

- Temperature

- Heat transfer Coefficients

- Results and discussion

Radiation from the Fuelbed

According to Fig.4.10, it can be stated that the temperature of the fuelbed is about 900 K when the excess-air factor is between 1 and 2. In order to calculate the radiative energy transfer from the fuelbed to the pan, we assume that the gases and flames between the pan and fuelbed do not absorb or emit any radiation. The view factor F between fuelbed and pan is equal to the view factor of two concentric parallel disks and can be found in many textbooks (see, for example, Sparrow and Cess 1970).

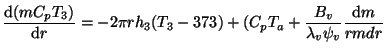

In order to check the estimated temperatures of the fuelbed and thus the radiative hat transfer to the pan, experiments were done by Herwijn with a radiative heat flux meter above a woodfire. The estimates of the fuelbed temperatures and the measured temperatures are presented in Table 5.1. The experimental results are obtained for a fire on a grate. The power density of the fire is 18 W/cm". In order to simulate a steady fire, the wood is added in small blocks. With such a procedure almost no distinction can be made between the burning of volatiles and charcoal. The temperatures are calculated from the measurements according to the following formula:

| (1) |

Here ![]() is the total radiosity arriving at the instrument.

is the total radiosity arriving at the instrument. ![]() the fuelbed surface,

the fuelbed surface, ![]() the view factor from fuelbed to the radiation

meter,

the view factor from fuelbed to the radiation

meter, ![]() the temperature of the fuelbed, and

the temperature of the fuelbed, and ![]() the temperature of

the radiation meter. The estimated temperatures are calculated according to

Eq.(4.15); for these calculations the excess air factor

the temperature of

the radiation meter. The estimated temperatures are calculated according to

Eq.(4.15); for these calculations the excess air factor ![]() is taken

to be 1. The differences in the estimated temperatures are due to the

variation of the power density on the grate.

is taken

to be 1. The differences in the estimated temperatures are due to the

variation of the power density on the grate.

In general, the measurements and estimated temperatures compare well. Although the measured temperatures with eccentric displacement of the meter are lower compared to the temperatures with a concentric situation, the deviation is within 15%.

| Sl. No. |

P (kW) |

b (cm) |

H (cm) |

e (cm) |

G |

||

| Measured | Estimated | ||||||

| 1. | 3.5 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 910 | 880 |

| 2. | 5.9 | 20 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 960 | 950 |

| 3. | 7.0 | 22.5 | 15 | 0 | 19 | 985 | 940 |

| 4. | 8.8 | 25 | 15 | 0 | 23 | 995 | 940 |

| 5. | 5.9 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 21 | 930 | 950 |

| 6. | 5.9 | 20 | 10 | 8 | 7.1 | 775 | 950 |

| 7. | 5.9 | 20 | 15 | 8 | 7.8 | 880 | 950 |

| 8. | 8.8 | 25 | 15 | 8 | 8.7 | 900 | 940 |

Using the above information we obtain the results for the radiant heat

transfer to the whole pan as shown in Table 2. The calculations are based

on a pan of 100 ° and the measured fuelbed temperatures

calculated form Eq.(1). The view factor is taken for a pan of 28-cm

diameter placed 15 cm above the fuelbed. The diameter of the fuelbed varies

with the power of the fire such that the power density is constant at 18

![]() . From the table it appears that 12% of the wood heat is

radiated to the pan.

. From the table it appears that 12% of the wood heat is

radiated to the pan.

| Sl. No. |

P (kW) |

Tb (K) |

|||

| (kW) | (%) | ||||

| 1. | 3.5 | 910 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 11.7 |

| 2. | 5.9 | 960 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 10.5 |

| 3. | 7.0 | 985 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 11.8 |

| 4. | 8.8 | 995 | 0.38 | 1.04 | 11.8 |

If we compare this to the efficiency achieved through common practice in developing countries - an open-fire efficiency between 10 and 15% - it can be stated improved stoves can only show a higher efficiency due to optimal use of the convective heat transfer.

Radiation from the Flames

One of the factors that determines the radiation from the flames is the emissivity. The total emissivity of the flames is a superposition of the contribution from the soot particles and the gases.

Emission of the soot particles

The emissivity of the soot particles is dependent on two quantities, the

flame height and the volume fraction of the soot particles in the flames.

When using an open fire, it is common observation that soot will deposit on

the cold pan. From experiments it appears that on the average about 5 g of

soot deposits on the pan when burning 1 kg of wood. With an excess-air

factor 3 we find a volume fraction for the soot particles of about 2.10![]() . This agrees reasonably well with experiments done in a closed brick

stove, where a soot concentration between 5 and 10

. This agrees reasonably well with experiments done in a closed brick

stove, where a soot concentration between 5 and 10

![]() of

the combustion products was found (Claus et al. 1981).

of

the combustion products was found (Claus et al. 1981).

Using the work of Felske and Tien (1973) to calculate the emissivity of the soot we find a value between 0.025 and 0.036 for a fire power between 3 and 8 kW.

Emissivity of the gases

Of the gases commonly present in a fire, only

![]() and

and

![]() contribute to the emissivity. The other gases (

contribute to the emissivity. The other gases (

![]() and

and

![]() ) consist of symmetrical molecules that emit and absorb

radiation only at much higher temperatures. In order to make an estimate of

the emissivity of the gases

) consist of symmetrical molecules that emit and absorb

radiation only at much higher temperatures. In order to make an estimate of

the emissivity of the gases

![]() and

and

![]() we will

assume that no incomplete combustion will occur and that the total

excess-air factor is equal to 2.

we will

assume that no incomplete combustion will occur and that the total

excess-air factor is equal to 2.

Hottel (1954) presents graphs from which the emissivity of the carbon

dioxide and the water vapor can be determined. Hottel also gives a method to

determine the mean beam length, depending on the volume, to be used with the

graphs. For our calculations we assume that the reference volume is a

circular cylinder with a radius equal to the radius of the flames at their

tips. The emissivity for the total gas radiation is listed in Table 3 as a

function of the power of the fire. In this table also the emissivity of the

soot particles is given.

| P (kW) |

h (cm) |

(cm) |

(m2) |

(W) |

(%) |

|||

| 1 | 8 | 25 | 0.016 | 0.035 | 0.050 | 0.016 | 61 | 6.1 |

| 2. | 10.5 | 3.2 | 0.021 | 0.041 | 0.061 | 0.028 | 128 | 6.4 |

| 3. | 12.3 | 3.8 | 0.025 | 0.045 | 0.069 | 0.038 | 200 | 6.7 |

| 4. | 13.8 | 4.3 | 0.028 | 0.049 | 0.076 | 0.049 | 280 | 7.0 |

| 5. | 15.1 | 4.7 | 0.031 | 0.051 | 0.080 | 0.059 | 348 | 7.0 |

| 6. | 16.2 | 5.0 | 0.032 | 0.053 | 0.083 | 0.067 | 417 | 6.9 |

| 7. | 17.2 | 5.4 | 0.035 | 0.055 | 0.088 | 0.076 | 503 | 7.2 |

| 8. | 18.2 | 5.6 | 0.036 | 0.057 | 0.091 | 0.084 | 575 | 7.2 |

| 9. | 19.0 | 5.9 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.095 | 0.092 | 659 | 7.3 |

| 10. | 19.8 | 6.1 | 0.039 | 0.060 | 0.097 | 0.099 | 724 | 7.2 |

The total emissivity of the flames

In order to calculate the total emissivity of the flames one has to

determine the effect of mutual absorption of the radiation from the gases

and soot. Tien et al. (1972) give a simple formula to calculate the total

emissivity

![]() when both soot emissivity

when both soot emissivity

![]() and gas

emissivity

and gas

emissivity

![]() are known. This formula is

are known. This formula is

| (2) |

In Table 3 the total emissivity is listed; also the total luminous

radiative power ![]() is given. We see that the flame radiation is

about 7% of the total power of the fire. For these calculations an

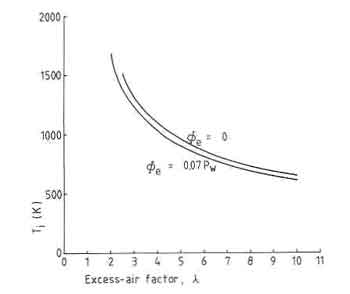

excess-air factor for the volatiles is taken to be 3. According to Fig.1

the average gas temperature for this situation is about 1400 K. Now that we

know the part of the power of the fire that is converted to the radiation of

the flames, we can revise the solution of Eq. (5.17). This is approximated

by

is given. We see that the flame radiation is

about 7% of the total power of the fire. For these calculations an

excess-air factor for the volatiles is taken to be 3. According to Fig.1

the average gas temperature for this situation is about 1400 K. Now that we

know the part of the power of the fire that is converted to the radiation of

the flames, we can revise the solution of Eq. (5.17). This is approximated

by

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the mass flow and the combustion value of the

wood respectively. The temperature of the gases becomes lower due to this

correction. The result is given in Fig.1. The (small) decrease in

temperature of the gases does not influence the emissivity factors listed in

Table 3.

are the mass flow and the combustion value of the

wood respectively. The temperature of the gases becomes lower due to this

correction. The result is given in Fig.1. The (small) decrease in

temperature of the gases does not influence the emissivity factors listed in

Table 3.

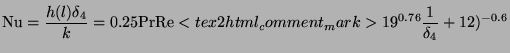

Fig.1. Gas temperatures for losses due to the radiation from flames

In experimental work the part of the flame radiation detected by the

radiative heat flux meter has to be estimated in order to check whether a

correction should be applied for this contribution. For this correction we

consider the source of the flame radiation to be circular, with equal power

in the total column and the same diameter. This source is placed in the

middle between fuelbed and meter. The part of the flame radiation impinging

on the radiation meter is determined by the view factor. Because this view

factor is for the given situation, of the order of 10![]() , no correction

is needed for the temperatures of the fuelbed.

, no correction

is needed for the temperatures of the fuelbed.

The contribution of the flame radiation to the heat transfer to the pan can be estimated in the same way. In this situation the view factor is 0.4, which means that due to flame radiation 3% of the total power impinges on the pan bottom.

Convective Heat Transfer to the Pan

Three factors determine the convective heat transfer to the pan on an open fire in a wind-free environment:

- (i)

- power level of the fire;

- (ii)

- the height between the fuelbed top and pan bottom; and

- (iii

- the pan-fuelbed geometry.

The efficiency of the heat transfer process can be defined in terms of ![]() , the exit temperature of the combustion gases (the average gas

temperature at the top plane of the pan), and

, the exit temperature of the combustion gases (the average gas

temperature at the top plane of the pan), and ![]() , the pan temperature.

When

, the pan temperature.

When

![]() , heat is carried away unutilized and when

, heat is carried away unutilized and when

![]() ,

the pan loses heat. A loss in efficiency is the result in either case.

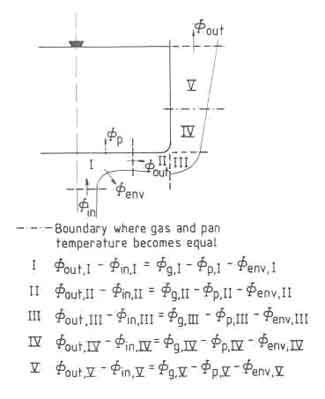

Figure depicts six hypothetical cases schematically corresponding to the

three factors mentioned above. For a well-matched power level of the fire,

the height of the pan above the fuelbed and the pan geometry

,

the pan loses heat. A loss in efficiency is the result in either case.

Figure depicts six hypothetical cases schematically corresponding to the

three factors mentioned above. For a well-matched power level of the fire,

the height of the pan above the fuelbed and the pan geometry ![]() will be

within a few degrees of

will be

within a few degrees of ![]() .

.

Fig.2. Among power level, distance between pan bottom and fuel bed and pan geometry

In order to make an estimate of the convective heat transfer from the hot

gases to the pan one has to know the temperature of the combustion gases as

well as the convective heat transfer coefficient. In general, the convective

heat transfer ![]() is given by the relation

is given by the relation

| (3) |

where ![]() is the heat transfer coefficient,

is the heat transfer coefficient, ![]() the concerned surface, and

the concerned surface, and ![]() and

and ![]() the gas and pan temperature, respectively. Before we present

estimates of temperature and heat transfer coefficients we first divide the

area around the pan into several subregions, each with its own flow

characteristic and a general method to estimate the gas temperature.

the gas and pan temperature, respectively. Before we present

estimates of temperature and heat transfer coefficients we first divide the

area around the pan into several subregions, each with its own flow

characteristic and a general method to estimate the gas temperature.

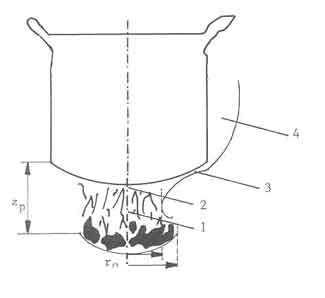

When we observe an impinging jet on a flat plate held normal to the jet, we

see a stagnation point region along the line of symmetry where the boundary

layer is expected to have constant thickness. Of course, this may not be

true in the presence of combustion. Beyond this region, over the outer half

of the pan bottom, the flow could be treated as an axisymmetric wall jet. At

the pan corner the gases turn again over an angle of ![]() due to the

buoyancy forces and will rise up along the pan wall. Figure 3 shows the

several regions; the bending of the flow around the corner of the bottom is

treated as a separate region and the flow along the pan wall is divided into

regions where combustion occurs and where no combustion occurs. For each

region a heat balance can be made. It will have the general form

due to the

buoyancy forces and will rise up along the pan wall. Figure 3 shows the

several regions; the bending of the flow around the corner of the bottom is

treated as a separate region and the flow along the pan wall is divided into

regions where combustion occurs and where no combustion occurs. For each

region a heat balance can be made. It will have the general form

| (4) |

Fig.3. es under and along a pan for which a heat balance has to be drawn

| I. |

|

|

|

| II. |

|

|

|

| III. |

|

|

|

| IV. |

|

|

|

| V. |

|

|

|

In words this means that the difference in energy content of the gas leaving

a region (

![]() ) and entering a region (

) and entering a region (

![]() ) is balanced by

the heat production due to combustion (

) is balanced by

the heat production due to combustion (

![]() ) minus losses to the pan

(

) minus losses to the pan

(

![]() ) and losses to the environment (

) and losses to the environment (

![]() ) whether due to

radiation or due to dilution by entrainment of air. In general, the

combustion stops in region IV, which means that in region IV the

contribution of

) whether due to

radiation or due to dilution by entrainment of air. In general, the

combustion stops in region IV, which means that in region IV the

contribution of

![]() is zero. In region III the heat losses to the

pan can be assumed zero because the pan surface exposed here is negligible.

The inlet temperature of each region is of course equal to the outlet

temperature of the previous region. As of now such a calculation, which

requires a complete numerical scheme, has never been attempted. There have

been several attempts to provide approximate results for the heat transfer

to the pan. The first one was due to Krishna Prasad et al. (1985) and a much

more refined version was provided by Bussmann (1988). We shall describe the

latter work in detail.

is zero. In region III the heat losses to the

pan can be assumed zero because the pan surface exposed here is negligible.

The inlet temperature of each region is of course equal to the outlet

temperature of the previous region. As of now such a calculation, which

requires a complete numerical scheme, has never been attempted. There have

been several attempts to provide approximate results for the heat transfer

to the pan. The first one was due to Krishna Prasad et al. (1985) and a much

more refined version was provided by Bussmann (1988). We shall describe the

latter work in detail.

Flow field

A schematic view of the fuelbed-flame-pan configuration is shown in Fig. 4 . The figure indicates the four regions of interest;

- a jet formed by the flame (1);

- the stagnation point flow region formed by the jet impinging on the pan bottom (2);

- the axisymmetric wall jet region formed along the pan bottom by the

gases turning by an angle of

/2 radians (3); and

/2 radians (3); and

- finally a two-dimensional wall-jet region along the pan wall (4).

Fig.4. w of fuelbed-flame-pan configuration

Available literature on modelling flow characteristics of impinging jets

uses the diameter of the nozzle exit (![]() ) as the characteristic

length. For woodfires the value of

) as the characteristic

length. For woodfires the value of ![]() is chosen to be the diameter of

the hot gas plume at the top of the flame. However when the distance between

the pan and the fuelbed (

is chosen to be the diameter of

the hot gas plume at the top of the flame. However when the distance between

the pan and the fuelbed (![]() ) is smaller than the flame height,

) is smaller than the flame height, ![]() is set equal to the calculated diameter of the fire at the pan height.

is set equal to the calculated diameter of the fire at the pan height.

Bussmann assumed that the stagnation point flow regime covers

| (5) |

In this region it is also assumed that no ambient air is entrained. This

assumption is based on the work of Era and Saima (1976) who investigated the

flow characteristics of an axisymmetric wall jet created by gases issuing

from a nozzle and impinging on a flat plate held close to the nozzle tip. In

the axisymmetric wall region there is an increase in the mass flow rate due

to entrainment of air from the ambient and is estimated from the

semi-empirical relation (Hertel 1962)

| (6) | |||

| (7) |

The flow field at the pan corner is difficult to describe. Thus Bussmann assumed that no air entrains at the corner and the flow develops into a two-dimensional wall jet as soon as it comes into contact with the pan side.

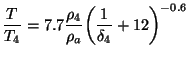

Temperature

The next step in the model is to estimate the temperatures prevailing in the different flow regions described above. The stagnation point region is divided into two regions.

(i)

![]()

![]() is the temperature at the pan height calculated from the flame model

presented in 5.2. According to this model

is the temperature at the pan height calculated from the flame model

presented in 5.2. According to this model ![]() is not a function of

is not a function of ![]() and thus is constant.

and thus is constant.

(ii)

![]()

The temperature in this region is evaluated from a simple heat balance

|

(8) |

The heat balance provides temperature as a function of radius and accounts

for heat loss from the gas stream to the pan. ![]() is the heat transfer

coefficient in this region.

is the heat transfer

coefficient in this region.

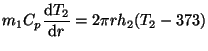

The temperature in the axial wall jet region

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the radius of the pan, is obtained from the quasi-empirical relation

provided by Hertel (Eq.5.21) and the following heat balance equation.

is the radius of the pan, is obtained from the quasi-empirical relation

provided by Hertel (Eq.5.21) and the following heat balance equation.

|

(9) |

The first term on the right represents the heat absorbed by the pan. The second term comes in two parts both associated with the entrainment of outside air. The first part simply accounts for the heat content of the entrained gases. The second part accounts for the heat liberation by combustion. Note that this term was absent in the stagnation point region. This is primarily due to the manner in which the flame model was implemented. That model is always computed on the basis of a chosen amount of excess air factor at every height. Since there is no additional air entrained in the stagnation region our flame model will not yield any heat release. The inclusion of heat release in this region is also questionable in the sense it is outside the calculation possibility of our flame model since it is only one-dimensional (that is, heat release occurs only as a function of height in the flame model; in the region below the pan the height is constant). Thus both cases - with and without combustion - was investigated by Bussmann. There is yet another consideration - volatiles coming out of the fuel bed should not all have been consumed before the gases arrive at the pan. Thus

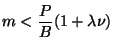

|

(10) |

![]() here represents the volatile fraction and

here represents the volatile fraction and ![]() is the excess air

factor. The last zone where temperature has to be estimated is in region 4

mentioned earlier. Bussmann assumed that the thickness of the hot gas layer

along the vertical side of the pan to be small in comparison to the radius

of the pan. This assumption permits the use of a relation proposed by Seban

and Back (1961) for a two-dimensional wall jet

is the excess air

factor. The last zone where temperature has to be estimated is in region 4

mentioned earlier. Bussmann assumed that the thickness of the hot gas layer

along the vertical side of the pan to be small in comparison to the radius

of the pan. This assumption permits the use of a relation proposed by Seban

and Back (1961) for a two-dimensional wall jet

|

(11) |

![]() in the above is taken as the temperature at the bottom corner of the

pan and is consistent with the assumption that there is no air entrained in

the corner. This probably will lead to an overestimate of

in the above is taken as the temperature at the bottom corner of the

pan and is consistent with the assumption that there is no air entrained in

the corner. This probably will lead to an overestimate of ![]() .

. ![]() ,

the thickness of the wall jet at the bottom corner, is calculated from

,

the thickness of the wall jet at the bottom corner, is calculated from

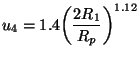

| (12) |

where ![]() is taken to be the velocity at the pan bottom corner. From the

work of Era and Saima, cited earlier, we obtain for

is taken to be the velocity at the pan bottom corner. From the

work of Era and Saima, cited earlier, we obtain for ![]() the following

relation.

the following

relation.

|

(13) |

Heat transfer Coefficients

In order to evaluate the various temperatures above and to estimate the total heat transfer to the pan, we need to know the heat transfer coefficients. These are the same as the ones used in Bussmann et al (1983) and reproduced here.

- (i) For the stagnation point region the Nusselt number relationship

proposed by Schlunder and Gnielinski (1976) is used.

(14)

(14)

denotes the average heat transfer coefficient.

denotes the average heat transfer coefficient.

- (ii) For the axisymmetric wall jet, the relation proposed by Hrycak

(1978) is used.

(15)

(15)

Re in Eqs. (5.29) and (5.30) is based on the length

.

.

- (iii) For the pan side the relationship given by Seban and

Back(1961) is used.

(16)

(16)Re here is based on the length, l, the distance along the pan side from the pan bottom.

Results and discussion

We will now present the results obtained from the above analysis. Fig. 5 presents the results of gas temperatures under the pan as a function of the radial distance.The three pairs of solid and dashed curves correspond to temperatures obtained for three distances between fuelbed and pan bottom - 0.1, 0.15 and 0.2m.

Fig.5. Distribution in the gas under the pan for different pan-fuelbed disaxial wall jet without combustion in axial wall jet

The pan radius for these calculations is 0.14m. The solid and dotted lines

denote respectively the cases with and without combustion being considered

in the axial wall jet. The discontinuity at ![]() is due to the fact

that a correction has been incorporated for heat absorption in the central

region of the pan bottom. The discontinuity at

is due to the fact

that a correction has been incorporated for heat absorption in the central

region of the pan bottom. The discontinuity at

![]() is due to the

fact that the axial wall jet relationship is applicable from this point

onwards. The result for the largest distance shows that there is no

combustion along the pan bottom at all due to the fact the volatiles have

been exhausted by the time the gases arrive at the pan bottom. Furthermore

at the lowest distance, the temperature at the bottom corner of the pan

drops to 500K in the absence of combustion. This is unrealistic. At this

height, even if we include combustion the temperatures at the bottom corner

does not even reach the values at the axis for the largest distance. Thus

considerable amount of combustion is likely to occur on the side of the pan.

According to our heuristic discussion in connection with Fig.2 this is

undesirable.

is due to the

fact that the axial wall jet relationship is applicable from this point

onwards. The result for the largest distance shows that there is no

combustion along the pan bottom at all due to the fact the volatiles have

been exhausted by the time the gases arrive at the pan bottom. Furthermore

at the lowest distance, the temperature at the bottom corner of the pan

drops to 500K in the absence of combustion. This is unrealistic. At this

height, even if we include combustion the temperatures at the bottom corner

does not even reach the values at the axis for the largest distance. Thus

considerable amount of combustion is likely to occur on the side of the pan.

According to our heuristic discussion in connection with Fig.2 this is

undesirable.

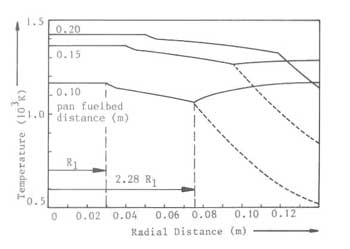

Figure 6 presents the average heat transfer coefficients over the entire pan as a function of pan-grate distance. These were computed on the basis of an average temperature difference between the gas and the pan. The figure shows an increasing heat transfer coefficient with increasing pan-grate distance. The experimental results of Herwijn on the contrary show a rather constant value. The difference must be attributed to the conditions for which the relations (5.28) - (5.30) were derived. For example the Schlunder - Gnielinski formula was derived for a turbulent jet with a distance between the nozzle and the plate being between the nozzle diameter and 12 times the value. The Reynolds numbers in the fires of interest here can be much smaller and the flow is probably not laminar but cannot be fully developed turbulent either.

fig. 6. Coefficient at the pan bottom as a function pan to fuelbed distance.

What is more the distance between the grate and pan bottom corresponds to the lower end of the limit prescribed by Schlunder and Gnielinski. Thus in calculating efficiencies a constant value of the heat transfer coefficient is adopted, but it will be varied parametrically.

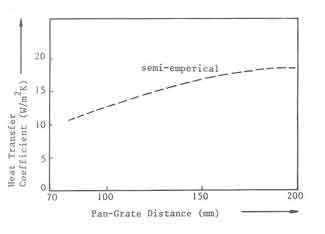

The next three figures (7 - 10) show some of the more significant

results obtained from the heat transfer calculation procedure presented

above. Fig.7 presents efficiency as a function of the pan-fuelbed

distance for three values of heat transfer coefficients, namely, 5, 10 and

15

![]() .

The flame parameters used in these calculations are:

the excess air factor

.

The flame parameters used in these calculations are:

the excess air factor

![]() ; the entrainment constant,

; the entrainment constant,

![]() ; and volatiles fraction,

; and volatiles fraction, ![]() . The fuelbed diameter is held

constant at 0.18m, the pan diameter is 0.28m and the combustion value of

wood is taken to be 18.7MJ/kg.

. The fuelbed diameter is held

constant at 0.18m, the pan diameter is 0.28m and the combustion value of

wood is taken to be 18.7MJ/kg.

The solid lines give the efficiencies obtained by including combustion in

the axial wall jet region while the dotted line shows the result without

combustion for the case with heat transfer coefficient of

![]() . The calculations incorporate corrections for the fuelbed thickness and the

so-called averaged peak power of the volatiles. The nature of these concepts

are discussed in connection with the experimental results to be presented in

the next section. The figure also shows the comparison of the theory with

experiment. It is easy to see the excellent agreement between theory and

experiment when one uses a heat transfer coefficient of 10W/m"K. In addition

it is also seen that it is important to account for the combustion in the

axi-symmetric wall jet region under the pan. This result confirms our

comment earlier on this question.

. The calculations incorporate corrections for the fuelbed thickness and the

so-called averaged peak power of the volatiles. The nature of these concepts

are discussed in connection with the experimental results to be presented in

the next section. The figure also shows the comparison of the theory with

experiment. It is easy to see the excellent agreement between theory and

experiment when one uses a heat transfer coefficient of 10W/m"K. In addition

it is also seen that it is important to account for the combustion in the

axi-symmetric wall jet region under the pan. This result confirms our

comment earlier on this question.

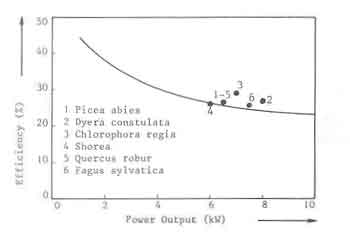

The next figure (Fig.8) compares the efficiencies obtained from

experiments carried out with different wood species and the theoretical

results. In the experiments the nominal power for definition;

also the next section) was held constant.

Fig.7.A function of pan-fuelbed distance. The points are from experiment the dotted line is without combustion for h = 10W/m2K.

Fig.8.a function of the power of the fire. Points are experimental results with different wood species.

However corrections have been introduced in the calculated efficiencies for the measured differences in the averaged peak power. For this reason the results are shown in terms of power output. The calculations have all been performed by assuming a uniform fuelbed thickness of 50mm. It is seen that calculated values are in good agreement with the experiments. The somewhat larger deviations from theory seen for species 2 and 3 must be attributed to the inevitable variations in the fuel bed thickness in the experiments (see next section).

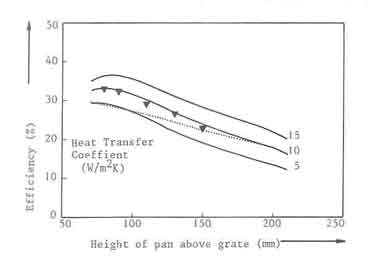

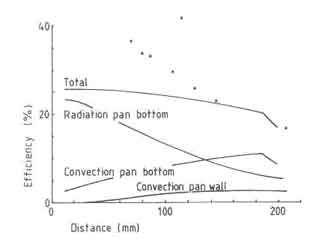

Finally Fig.9 shows a break-up of efficiency in terms of heat transfer by radiation and convection as reported by Krishna Prasad et al. (1985). The convective heat transfer is further divided into heat transfer to the bottom of the pan and the pan side. The heat transfer to the pan bottom above an open fire was measured with a heat flow meter by Herwijn (1984). This meter was placed such that the detecting surface lies in the plane of the pan bottom. The heat flow meter measures the radiant as well as the convective heat flux to the surface. Tests were performed for two powers of the fire, 6 and 8.7 kW; two distances between pan and fuelbed, 10 and 15 cm; and two eccentricities of the heat flow meter in the pan, 0 and 8 cm (the pan was always placed concentric with the fire). Table 5.4 gives a more detailed presentation of the measurements. The radiative contribution to the heat transfer found earlier can be subtracted from the total measured heat transfer. This gives an estimate of the convective heat transfer. These values are also listed in the table. The total, radiative, and convective heat transfer are related to the power of the fire in order to get the efficiency contribution of the various terms. The efficiency obtained for the convective contribution is obtained as before by dividing the pan bottom into two regions: the stagnation point region and the axisymmetric wall jet region. The radius of the boundary between the two regions is taken to be equal to the plume diameter calculated in the flame height model.

Fig.9. Efficiencies according to heat transfer by radiation and convection. Points are from experiments of Herwijn (1984)

In Fig. 9 the estimated efficiencies for a 6-kW fire are shown. Although

the measured radiative contribution agrees well with the model, as already

was shown in Table 2, the convective contribution to the pan bottom does

not agree at all. The main reason for this disagreement is the assumption

that the combustion stops at the pan height. This has been corrected in the

work of Bussmann.

| Sl. No. |

P (kW) |

(cm) |

(cm) |

(cm) |

(kW/m2) |

(kW/m2) |

(kW/m2) |

| 1. | 6.0 | 15 | 20 | 0 | 32.4 | 17.5 | 14.9 |

| 2. | 5.8 | 15 | 20 | 8 | 25.8 | 17.9 | 7.9 |

| 3. | 8.8 | 15 | 25 | 0 | 37.1 | 14.4 | 22.8 |

| 4. | 8.6 | 15 | 25 | 8 | 28.2 | 19.5 | 8.7 |

| 5. | 5.9 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 37.9 | 21.0 | 16.9 |

| 6. | 6.0 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 32.5 | 25.5 | 7.0 |

The point about this earlier work is it clearly establishes the relative importance of radiative and convective heat transfer to the pan. At the low height the radiative heat transfer contributes as much as one-third of the total heat input to the pan. At larger heights the importance of radiation goes down, A second point of importance that emerges from this figure is the fact that the convective heat transfer to the bottom and side of the pan are of equal orders of magnitude. Thus many a multi-pan improved stove with a chimney do not provide for heat transfer to the pan sides. Of course they do provide additional heat transfer surface by adding more pans. But that makes the stove bulky. Hence it is important to clearly delineate the merits of such stoves in comparison to single pan stoves that provide for adequate heat transfer surface.

total stove system